The Truth About the U.S. Deficit (Part 2)

How Bad Is It, Really?

📌 The Quick Hit

Following last week’s article on the truth about who actually holds U.S. debt, we turn to how bad the deficit dilemma is.

The U.S. deficit feels alarming mostly because big numbers rattle us.

Historically, deficits don’t forecast recessions, and surpluses don’t guarantee strong markets - quite the opposite in several cases.

The real lens isn’t the raw debt figure; it’s the balance sheet: assets, liabilities, and scale.

By that measure, the U.S. remains enormously wealthy.

🥁 The Treasury’s Drumbeat (Or Pause Button)

The Treasury’s monthly surplus/deficit report is due out this week - a bureaucratic fireworks show for finance nerds. But last week’s notice hinted at delays: “due to a lapse in funding,” a wonderfully circular explanation.

Late or not, here’s a safe bet: the U.S. is still running a sizeable deficit.

And yes, that bothers us. But why, exactly?

In the English-speaking world, debt was long cast as a moral failing. An ethos inherited from ancestors who preached, “owe nothing, ever.” Benjamin Franklin’s scolding adage didn’t help.

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” ~ Benjamin Franklin

So when Uncle Sam borrows, Americans (and much of the rest of the world) instinctively hold our breath.

“How will we repay it?”

“Won’t deficits trigger recessions?”

“Surely high debt torpedoes markets?”

Let’s interrogate those assumptions, by asking appropriate questions.

🌊 Do Deficits Trigger Recessions?

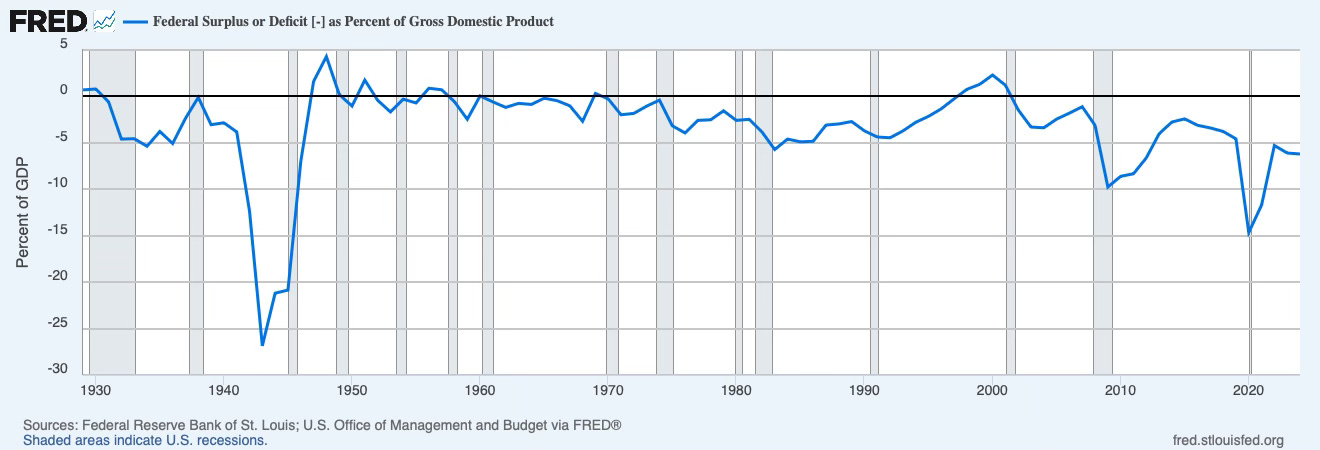

A century-long chart of U.S. surpluses/deficits (as a percentage of GDP) tells a surprisingly placid story: there is no meaningful correlation between running deficits and sliding into recession.

As shown below, anything above the black line is surplus, and below is deficit. Gray indicates periods of recession.

In fact, recessions often emerge after periods of surplus - notably 1948, 1957, and 2000, each followed closely by economic downturns.

Deficits, even steep ones, do not reliably signal contraction ahead.

📉 Do Deficits Hurt Stock Markets?

If deficits crushed markets, the past 50 years should show it.

Instead, only four years in that span saw federal surpluses - 1998 through 2001 - and they culminated in:

the tech bubble’s implosion

a recession

a long, grinding bear market

Not because surpluses cause crashes, but because they tend to appear at the top of exuberant cycles.

👉 Meanwhile, markets typically deliver ~29% cumulative gains over the 36 months following deficit extremes.

Again, counter-intuitive, but clear.

👻 Why Big Numbers Spook Us

Trillions feel cosmic, impossible to wrap the mind around.

So we react emotionally, not analytically.

But scale matters.

Debt should be viewed relative to economic output and assets.

U.S. federal deficits currently hover around 5.8–6.4% of GDP—large, yes, but far from catastrophic when measured against the enormous U.S. economic engine.

To help internalize this, think in personal terms:

Bob’s net worth + income: $500,000

Bob’s total debt: $100,000

Debt ratio: 20%

By comparison, Bob is arguably more leveraged than the United States.

⚖️ The Balance Sheet Reality

Raw debt figures don’t tell the story. The national balance sheet does.

This includes:

federal real estate, natural resources, gold, intellectual property (≈ $6T)

state and local assets

private-sector wealth

All in, America’s estimated asset base is ~$269 trillion.

Liabilities? ~$150 trillion.

Approximate national net worth: $125 trillion.

That is the backdrop against which deficits exist.

Yes, the scale is staggering! But the reality of the U.S. balance sheet should be stabilizing.

✨ Key Takeaways

Context is king. Debt by itself is meaningless without the balance sheet to measure it against.

Deficits don’t doom economies. Historically, they coexist with growth; surpluses often precede slowdowns.

Don’t let size scare you. Trillions look monstrous in isolation but modest when set against a $25-trillion-plus economy and a $125-trillion national net worth.

When in doubt, zoom out. The U.S. remains an extraordinarily wealthy nation capable of supporting its borrowing habits.

🚀 Up Next:

Sunday - “I Can’t Afford to Lose My Money!””

Thursday - “Reasons to Be Grateful”

This publication is for brains, not bets. The Other Side of Obvious shares ideas, stories, and general financial information—not personalized investment, tax, or legal advice. Investing comes with risk (including losing money). Talk to a pro before you act. Please take time to read these important disclosures before you get started.